Early New England Dancing

|Both contradancing and square dancing have been popular throughout much of the country for a long time. Contradances can be traced primarily to the English tradition of longways (line) dances, whereas squares can be traced primarily to the French quadrilles (four-couple dances done in square formation). The balance of popularity of the two has shifted over time and from place to place. After the War of 1812 the balance shifted toward contras in New England and toward quadrilles (squares) in much of the rest of the country. This has been attributed to the support for the English in New England, and support for the French in most of the rest of the country.

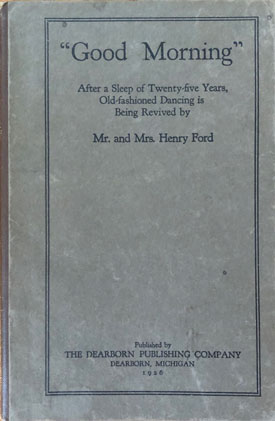

In the 1920s Henry Ford started a program of American folk dancing (including contras and squares) in Michigan, which included fiddling contests and even a book of dances called Good Morning. His reasons for supporting traditional dancing were far from admirable: he wanted to counter the influence of jazz for largely racist and xenophobic reasons. But considerable good music and dancing resulted despite the unfortunate justification.

Rising Popularity of Square Dances

During this time square dancing became very popular throughout most of the country, and as amplification became more practical, many callers started calling singing squares in which the calls were sung to popular songs of the day as well as classics like Golden Slippers and Darling Nelly Gray. Squares were commonly danced in sets of three. They were generally danced in alternation with sets of round dances — couples dances such as waltzes, polkas, schottisches, foxtrots and others. At some dances a round dance set might consist of three waltzes or three polkas; at other dances each round dances in a set would be different. At some dances there might be one or two contradances in the cycle as well; that became less common as time went on. The first edition of Good Morning, published in 1925, contained mostly contras and quadrilles. By the fourth edition in 1943 these were considerably less numerous, and instead there were many singing squares and round dances.

During the 1940s and 1950s the western style of square dancing became more popular. These included singing squares and squares done to a more patter style of calling. They gradually became more complex, and started requiring lessons before dancing in a set. That was the start of club-style Western square dancing which was popular for many years.

In parts of New England contras generally remained popular, although singing squares were popular too. In New Hampshire and Maine contras probably were most popular, whereas in Vermont and western Massachusetts singing squares were more popular at times. In New Hampshire Ralph Page kept contras alive in the 1930s through the 1950s along with being known for his singing squares. In Vermont the Ed Larkin dance troupe kept the contras alive.

But by the end of the 1950s and early 1960s there wasn’t much traditional dancing going on. In much of New England (and the rest of the country) people were busy watching television and doing other more “modern” activities, and had no time for participatory “old-fashioned” events like contra and square dancing. The dancing nearly died out except for in a couple places, mostly isolated where there was no television reception. The best known was the Monadnock region of New Hampshire, where television reception was nonexistent and dancing remained strong. Ralph Page and Duke Miller were doing dances regularly to excellent live music. Ted Sanella revived/kept dancing going in the Boston area.

The Contradance Revival

In New Hampshire Dudley Laufman became a major leader of dances. He called a lot in the Monadnock region along with Ralph Page and Duke Miller. His dances started to attract many from the back to the land movement, and started to become very popular. At the time Dudley had fewer rules and restrictions at his dances than the others, and people loved his dances. He started to attract some of the best musicians around too, leading to the formation of the Canterbury Country Dance Orchestra. As I understand it, you could be pretty sure if you went to a Dudley dance that the music would be good, and probably the dancing as well.

Gradually contradancing started spreading out into the rest of the country from New Hampshire. People who danced to Dudley would move away and miss the contradancing. They learned to call and play music, often supported by local musicians, and started dances in their new home towns. By the late 1970s and early 1980s contradancing had spread through much of the country.

With increased popularity, people started writing more and more new dances and fiddle tunes. I've heard a similar story from several of the old-timers. After years of playing for large enthusiastic groups of dancers they watched the music and dance gradually fade away. Some of them even stopped playing for a couple decades.

Lucien Mathieu was the uncle of the great fiddler Don Roy from Maine, and the one who taught Don to play the fiddle. He was one of those people who experienced the decline of interest in his music. At one point he was invited to come to Maine Fiddle Camp to do a couple workshops. His response was that a he didn't think anyone would be interested in what he had to offer. He was very surprised to see a few hundred fiddlers at camp, many of whom were kids and teenaged fiddlers. And we all were very interested to hear him play and to learn from him. He liked it so much that he became an enthusiastic member of the Fiddle Camp community. I think he came back every year until health prevented it.