New Hampshire Old-Time Country Dance Web Site

Passing On Our Living Tradition

The New England Tradition: Change & Preservation I

The New England Country Dance is a living, changing tradition. Here I present some observations, stories and thoughts about how over time some aspects of the tradition remain relatively unchanged, whereas others change quite substantially. I discuss this in terms of behavioral psychology concepts.

Much of this is based on an eight-part series of articles published in the Seacoast Country Dance Newsletter between February 1995 and January 1996. I did major revision and editing in November, 2019 and further revision and editing in May and October, 2020.

On This Page

- Introduction. Discussion of how some aspects of the New England dance tradition (and undoubtedly most others) remain fairly stable whereas others change, sometimes fairly rapidly.

- Change & the Selection Process. I introduce the concept of selection from behavioral psychology and evolutionary theory as a useful concept in discussing the degree and type of change that occurs.

- Behavioral variability among dancers, musicians & callers. And then there's the role of variability in the behavior of members of each of the three major groups at a dance.

Introduction & Examples

Introduction

The series of articles underlying this page was originally inspired by the 1995 Ralph Page Legacy Weekend in Durham NH and by the journal Contra and Square Dance History published by Michael McKernon quarterly during 1995 and 1996.

I’ve been thinking about some of the changes in New England traditional dance over they years, and trying to fit together various observations and bits of knowledge and speculation I’ve encountered over the years.

Before getting any further into this topic, I need to establish several points. The first few deal with my approach to the topic.

- This is a topic that’s been studied at length by folklorists, ethnomusicologists and historians. I am none of those. I am a behavioral psychologist by profession, who has participated in New England Country Dance for the majority of my life in all the major roles: dancer, musician and dance caller.

- As such I think I have some worthwhile observations and insights on the matter. However I also recognize the dangers of trying to discuss a topic in a field outside one’s area of expertise.

- To avoid that, I will present a number of observations, and my interpretations will make use of concepts from behavioral psychology and related evolutionary concepts which I believe are useful in this context.

Contradancing is a living tradition and changes over time

Having said that, here are some broad observations about New England country dance.

- Contradancing is a living tradition. It goes back in its roots several hundred years, and it’s still being done. As with any living tradition it changes to fit the needs of the current musicians and dancers.

- This is a good thing: if it stopped adapting it would probably become a period performance art rather than something that we did just for fun.

- That doesn’t mean that all changes are good, or that everyone has to like the way things are going.

- In the past couple decades [from 2020] it seems like the overall pace of change has accelerated markedly; I’m not sure this is a good thing in the world of traditional music and dance, but we have to make the best of it we can.

- We can try to direct the changes, but my feeling is that it’s very difficult to change trends that often reflect changes in the society and culture at large.

But parts of the tradition are passed on with little change

From September 1992 to February 2019 the Lamprey River Band played a monthly dance in the Dover City Hall. Nearly every time we did a dance I would spend at least a few minutes looking out at the dancers and thinking about how many years earlier, in the 1940s and 1950s, there were also monthly dances in that hall. They were called by people like Phil Johnson, Mal Hayden, Ralph Page and Guy Mann. I knew Phil for years and met Guy Mann’s wife after he died; she came to the dance to see if I wanted any of his square dance materials, and we picked them up at their apartment in Dover. The musicians for the dance included Marcel Robidas, Milt Appleby and Joe Pomerleau, all friends I’ve played music with many times, and others I heard about from them. The dancers I’m less sure about, but I believe Paul Kanaly used to dance there and maybe others.

Here is your editor calling in Dover on 2/5/09, with Burt Feintuch on my left. Photo by Linda Saucerman. (I'm pretty sure I got permission to use it but Linda, if you see this feel free to get in touch.)

I would think about how they did many of the same dances we do now, often to the same tunes we use for them today, and called by some of the people who were my role models for learning to call. Suddenly history isn’t something you read about in a book; I was experiencing and participating in history myself!

The Dover dance isn’t happening any more, but we’re doing the dance in the Durham Unitarian Universalist Fellowship. When I first started dancing in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Dudley Laufman did a monthly dance there which I attended. So it was pretty amazing when Dudley showed up and called a couple dances at our first dance in the hall. And now I think about how I call some of the same dances there that Dudley called 40 years ago, again often to the same tunes. The big difference is that I was actually there, and remember him calling those dances that I am now calling in the same hall to the same tunes.

Although aspects of the dance may have changed

Think about some of the older dances you have danced. Some of them are clearly among the most fun dances around. In my opinion a list of such contras would include Chorus Jig, Hull’s Victory, Sackett’s Harbor, British Sorrow, Lady of the Lake, Money Musk, and actually quite a number of others. However, if you look through a book of dances from say 100 to 125 years ago [1995 reference], you’ll probably find many other dances that appear at best to be worth doing out of historical curiosity. And I say this as someone who overall is probably much more fond of the older dances than many. Even most of the older dances that are popular now once were done differently. Nearly all the old favorite dance were done in ways most modern dancers would consider less exciting.

Chorus Jig

As danced in the 1890s:Down the outside & back

Down the center & back,

Cast off

Turn country corners

Actives balance &

Turn to place

Country corners would probably

be pass right shoulders with

partner, turn first corner by the

right, and repeat. It would end

with balance twice and turn

both hands to place.

As danced today:

Down the outside & back

Down the center & back,

Cast off

Turn country corners

Actives balance & swing

Country corners are turn

partner by the right, turn

first corner by the left, partner

right and second corner left.

In fact, sometimes I have wondered why dancing was ever all that popular given the obviously boring qualities of a number of older dances. If that’s what they did a hundred or two hundred years ago, it seems like they couldn’t have had that much fun. A look in dance books from a century ago produces a long list of plain quadrilles that, at least on paper, often seem rather uninspired. But yet, the kind of dancing we do was historically considerably more popular than it is now. In past years many more towns had their own dances, generally weekly rather than monthly. In the middle of rural New Hampshire, the Bradford dance attracted hundreds of dancers every weekend for decades.

One might attribute that to the slower pace of life, or to the dancers being less sophisticated. But consider the fact that contradancing appealed to people like George Washington, whose favorite dance was the Virginia Reel which is now considered boring by many dancers. No one could consider George Washington a simple rural person of simple taste who led a dull life.

In the next section I will present some concepts that may appear to be questionably relevant but I think say something about what’s going on.

Selection Procsses

Change & the Selection Process

In this section I’ll try to provide a way to look at how some aspects of a tradition get passed on with great precision and others end up changing substantially over time. As I said in the previous section, I will use some concepts from my field of behavioral psychology and some related evolutionary concepts to organize my ideas.

The selection process and its importance

Presumably everyone is at least familiar with the concept of natural selection in the context of evolution of species. There are two main concepts.

- A species exhibits variability with respect to many/most characteristics. Some of these variations will either increase or decrease the likelihood of an individual possessing them surviving to reproduce and pass on those characteristics.

- If a particular variation results in a creature (or plant for that matter) having a better chance of surviving to reproduce, it is selectively passed on. Over many generations, this can cause a marked change in that characteristic in a species.

- As it happens through natural environmental forces, this is called natural selection. Note that when developing a new variety of tomato or corn, people deliberately cause selection processes to happen; this can be called artificial selection.

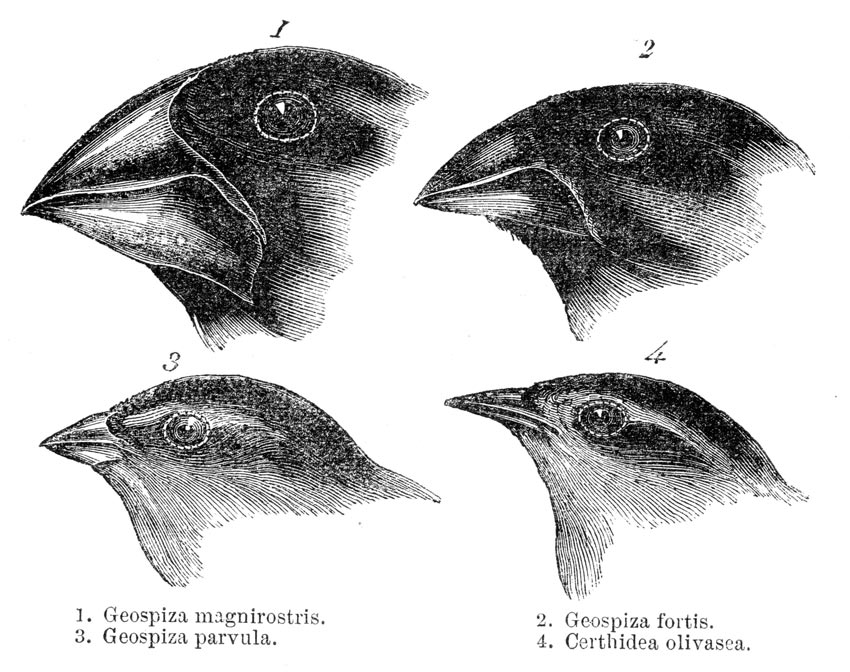

Four species of finches from the Galapagos Islands, each adapted to a slightly different environment.

The classic example is the finches of the Galapagos Islands (sometimes known as Darwin’s Finches). The Galapagos Islands are over 600 miles off the coast of Ecuador. Being isolated, it’s much harder for a species to find its way out there. So when at some point long ago some finches made their way to the islands, there were a variety of habitats available. Different habitats contained different food sources. Thus, in each environment different characteristics were beneficial for survival and reproduction.

Finches in some settings found crunchy seeds and arthropods; in other settings there were insects to be found hiding in the foliage. The first setting selected for finches with beaks capable of crunching their food (finches 1–3); the second selected for long thin beaks capable of reaching for hidden insects (finch 4). Obviously this is a simplified explanation, but it should do for now.

Behavioral psychology & selection on the dance floor

The principle of natural selection is generally applied to generational changes in a characteristic. But a very similar concept is used by behavioral psychologists to talk about changes in an individual’s behavior over time.

- Most of our behavior exhibits some amount of variability. We don't do things exactly the same each time.

- Much of the time our behavior has consequences: something happens as the result of what we do. Often these consequences result in us being more or less likely to repeat the behavior when similar circumstances come up again. Sometimes the consequences of our behavior also increase or decrease the amount of variability we exhibit in how we do things.

- Consequences of our behavior that make it more likely to occur again in similar circumstances are called reinforcers.

- When consequences make the behavior less likely to occur again in similar circumstances, they are called punishers.

- When the consequences of our behavior affect its likelihood of occurring, that’s referred to as a selection process.

Applying this to contradancing, if a dance caller calls a new dance and it’s received well, he/she will probably call it again. If the dance produces less favorable outcomes (lack of enthusiasm while dancing, lack of applause, etc.), the caller likely won’t call the dance as much in the future. (In behavioral terms the first outcome is an example of reinforcement, and the second is punishment.) You may notice that this is pure selection; I’ve left out the role of behavioral variability here; we’ll get to that later.

I should think all callers have called a dance for the first time to an enthusiastic bunch of dancers, and all dancers have had the experience of dancing a dance for the first time and loving it. Chances are that everyone in the traditional dance community has had the experience of calling/dancing a dance for the first time and being less than impressed.

Selection & The Evolution of the Dance

The selection process, together with behavioral variability (discussed in the next tab), affects all aspects of the dance. The figures and their timing have changed over the years as a result of selection processes. The choice of tunes and the style of playing tunes is changing continuously as the result of selection. And the style in which the figures are danced changes over time as the result of selection.

On the Evolving Chestnuts page I look at how several of the well known chestnuts have changed over the years as a result of the combination of behavioral variability and selection.

A look at the quality of dances and a brief digression on selection

Let's imagine we've gone to a dance, and on the way home we're discussing it. Our perception of and enthusiasm for a dance is simultaneously being affected by many variables. As I mention elsewhere, these might include the quality and nature of the calling and the music, the overall skill level and enthusiasm of the dancers, your partner for that dance, which friends did or didn't show up, and lots more. All these variables combine in complex ways to affect how we feel about a dance or an evening of dancing.

As a result of how all these variables combine we might be very enthusiastic in our discussion or we might be inclined to go to another dance with the same caller and/or band even when far away or in bad driving conditions — or we might not. This is the selection process in action in the dance setting.

The selection process is affected by all these variables simultaneously, so it's very complex and hard to analyze in the real world. So let's do what scientists generally have to do to make a topic approachable, and simplify.

To make this more approachable, let's consider one variable in isolation: the quality of the dances called in an evening. Some dances are just so much fun to dance and call. For example, Chorus Jig, Rory O’More, Shadrach’s Delight, and many others would fit this category. But if you consider the total number of dances, very few are in that category. Many more are OK but not great, or even not very good. Suppose we took a large sample of dances that might be called at a contradance and rated each one. We might come up with something like what’s in the top panel of the graph below.

If a caller were to start calling from that pool of dances, some would get better responses than others, which would act as reinforcement for calling the more fun dances and punishment for calling the more boring dances. But quite a few dances would be somewhere in the middle as shown: not inspirational, but not all that bad. They probably wouldn’t produce very strong feedback one way or another, so a caller might keep calling them, but maybe not all that frequently.

This feedback affects the caller's choice of dances. As a result of this section process after a while the caller would likely end up calling the popular dances more frequently and the unpopular dances less frequently. This would produce a pattern more like what’s shown in the bottom panel of the graph.

This process of selection of behavior through its consequences (reinforcement and punishment) is an important determinant of our behavior, and has shaped the dance selections of every caller who has called for dancers.

Here’s the brief digression. The well-known chestnut contras are generally really good and creative. There are a whole ton of modern dances that seem to consist of swing the one below (the progression), do some generic figure, and swing your partner. Not terrible but not inspirational; and a whole evening of them can seem rather boring. Are people less creative or less skilled in composing dances now? Probably not. Rather, the older dances have already been through the selection process, and mostly the best ones are still called. Selection has had less chance to act on more modern dances, so many of the lower quality dances are still being called. I’d guess the older ones seem more creative because they represent the best of dance composition over many years of varying stylistic preferences, whereas the modern dances would tend to reflect a much narrower set of influences.

Variability

Behavioral variability among dancers, musicians & callers …

In the previous section I showed a graph of the hypothetical quality of dances based on a large sample of available dances (top panel) I show a preponderance of mediocre dances and a smaller number of really good ones, which is probably accurate. Behavioral selection alone can account for the disappearance of most mediocre dances from the repertoire as described in the previous section (bottom panel). There are so many good ones that why dance the mediocre ones. You’ve likely experienced that yourself if you’ve been dancing for a while: new dances come along and are called a fair amount at first, but then gradually fade into obscurity.

But things are more complicated than that. In reading an article in Michael McKernan’s journal, some ideas I’ve had for a while started to solidify. As any dancer should be able to understand, the dance as written is really only the basic framework of the dance as actually danced. There are at least three aspects to this, each of which is subject to considerable variability.

Let's start with the music. The written music for most dance tunes is only a framework around which musicians, each with an individual style, build variations and harmonies to fill it out. Compare a dance tune played by a good fiddler who knows the tradition well with the same tune played by someone who is unfamiliar with the tune and the tradition and is reading the music out of a book. Even if the person has excellent reading skills the difference will be obvious. How the tune is played can have a profound effect on how the dancers dance.

The second aspect would be the caller. Some callers read from their cards; some callers don't use cards because they know the dances and don't need them. Some callers are more relaxed, move differently, have a showy style or a more low-key style; callers differ in many ways. The same person could differ substantially depending on outside factors. How the caller calls the dance also has a profound effect on the dancers.

Then there are the dancers themselves. In addition to responding to the music and the calling, different dancers have different styles. If someone were to add in some dance moves that weren’t part of the dance, that might make even a boring dance suddenly be fun.

All of these differences would be examples of behavioral variability. For the dancers, that variability could take the form of minor improvisation, or it could take the form of fairly radical changes to a dance. Of course, variability doesn’t always make something better. Many of us have had the experience of trying something new that just didn’t work. Probably most of us have experienced the results of someone else trying something new that disrupted the dance, sometimes badly. Likewise I've heard music played with very unclear phrasing, no distinguishable rhythm and even without clear melody. But sometimes several factors come together and produce an evening of outstanding music and dance.

Tod Whittemore calling (dancing in this photo) in Fitzwilliam with the Sugar River Band, 8/4/12. This was one of those dances where everything came together to produce an outstanding evening of dancing.

Types of Variability

There are undoubtedly many ways in which the variability of behavior can be classified. I'd like to mention one important way in which behavioral variability can be discussed. Some changes in behavior are along a continuum. It occurs in greater or lesser degrees. For example, the quality of dances, as used on the page about selection, varies continuously. It can be broken down into categories as i did, but those are arbitrary. Other examples involve changes of a more discrete (as opposed to continuous) nature. There are real categories rather than just taking a continuous variable and making up arbitrary categories. For example, in Petronella, the change from only the actives dancing to everyone dancing in the "round to your right and balance" part of the dance is a discrete change: it's either one or the other. These discrete changes are very much analogous to the evolutionary concept of a mutation. As in biology, some mutations are successful (as with the dance Petronella), but there are many things that people try that just don't catch on.

Style of Dancing

I’ve mentioned that some of the older dances, especially those found in older dance manuals and not danced frequently these days, appear not to be very interesting. Some of them probably were danced a few times and then dropped out of the repertoire. But some appear in a number of dance manuals so likely were fairly widely danced. So let’s think about how people fill out dances to make them more fun and interesting, to the point where they continue dancing them sometimes for generations.

Useful Classes from Site Styles

Backgrounds:

- .bg - gradient

- dark-bg-100 - dark blue-green 100%

- dark-bg-10 - dark blue-green 10%

Font Color Names:

- dark-red-brown

- red-brown

- dark-blue

- dark-blue-green

- dark-blue-green-10

Columns:

- col - two column

- col3 - three column

- col-wide - min width 500px

- together - put <div• class = "together"> around header & paragraph (remove •)

Paragraph Styles

- tenmed - ten body

- close-para - height 1.2 em

- center - text-align center

- left-sub - ten large h5

- center-sub -ten h5

List Styles

- Level 1 (Green Star) - no class needed

- Level 2 - triangle

Margins & Padding

- margtop - 20px

- margbot - 20px

- padtop - 8px

- padbot - 8 px

- margleft - 24px

- padleft - 24px

- nopads

- nomarg

- negtopmarg - 32px

- negbotmarg - 32px

Borders & Lines

- hr.blue-line - top border 1px column-span all, width 80%

- hr.blue-line-no-span

- top-bor - 1 px dark blue

- coldiv - right border 1px blue-green 25%

- firstcharacter - drop cap

Color Hex Names

- Dark Blue-Green: #003840

- Dark Blue Green 10% Opaque: #E6EBEC

- Dark Blue-Green 25%: #C0CED0

- Dark Blue-Green 50%: #809CA0

- Dark Blue: #070A58

- Dark Blue 10%: #070A58

- Blue Green: #0C5A5B

- Dark Red-Brown: #400610

- Red-Brown: #590202

- Gradient: Dark Blue-Green (100% opacity) to Dark Blue Green, 85% at 0% opacity

Other Useful Information

Useful Typinator Abbreviations

- Links:

- Markup link: .<link

- HTML Link: .<a

- .<rec = <img src= [Macro here] align="center" alt= [Description Here] />

- .<res = <img src= [Macro here] alt= [Description Here] />

- Others:

- .ul and ./ul = begin, end unordered list

- .ol and ./ol = begin, end ordered list

- .li and ./li = begin, end list item

- .<x = enter begin code, text, same end code with automatic "/"

- .<2x = enter begin code, text, different end code with automatic "/"

- .<BI = beginning and ending Bold Italic

- .<p = beginning and ending of paragraph text

Links

- To open a link in a new tab or window, use target="_blank"

- For example: <a href= [URL path in double quotes] target="_blank">RPLW Syllabus, 1988 (PDF)

Relative URLs

- Sample Directory

- Home

- RPDLW

- Living Trad

- Passing On

- Evolving

- Home

Relative URL assumes the first part of the URL is the same as the current location so only put path or URL relative to where you are in the folder structure

- To get back to the root folder use slash (/)

- To link to Home from any page: <a href="/" [end bracket] Home </a & ">"

- To link to Home from any page: <a href="/" [end bracket] Home </a & ">"

- If the link is in the same directory as the page from which it's being linked, just give the name of the page being linked to:

- To link to Passing on Traditions from Evolving Chestnuts:

<a href="passing-on-tradition-I/"> Passing On I</a>

- To link to Passing on Traditions from Evolving Chestnuts:

- If the link is in a subdirectory of the page from which it's being linked, give just the name of the page being linked to:

- To link to Petronella from Evolving Chestnuts:

<a href="petronella/"> Petronella</a>

- To link to Petronella from Evolving Chestnuts:

- If the link is in a higher directory than the page from which it's being linked, use "../" which means go up a directory:

- To link to Living Tradition from Evolving Chestnuts:

<a href="../dance/"> Dance </a> - To link to RPDLW from Evolving Chestnuts:

<a href="../../ralph-page-dance-legacy-weekend/"> RPDLW</a>

- To link to Living Tradition from Evolving Chestnuts:

- If the link is at the same level under a different directory than the page from which it's being linked, use "../" and the name of the directory:

- To link to RPDLW from Passing on Living Tradition:

<a href="../ralph-page-dance-legacy-weekend/"> RPDLW</a>

- To link to RPDLW from Passing on Living Tradition: